Lesson 4: Working with Text & Data

recording:

Lesson 4 (US Morning) YouTube | FileBase

Lesson 4 (Europe) YouTube | FileBase

Lesson 4 (US Evening) YouTube | FileBase

objectives:

"Use lists to organize data."

"Convert between kinds of lists (e.g. tapes)."

"Diagram lists as binary trees."

"Operate on list elements using

snag,find,weld, etc.""Import a library using

/+faslus.""Create a new library in

/lib.""Review Unicode text structure."

"Distinguish cords and tapes and their characteristics."

"Transform and manipulate text using text conversion arms:

"Interpolate text."

"Employ sigpam logging levels."

runes:

"

/+""

~& >>>"

keypoints:

"There are four basic representations of text in Urbit: cords, knots, terms, and tapes."

"Lists organize data for collective analysis or application."

"There is a suite of tools for working with lists."

"A library is an importable core of code."

"Gates that produce gates (like

listv.(list)) form an extremely common and important pattern in Hoon."

homework:

Text in Hoon

We've incidentally used 'messages written as cords' and "as tapes", but aside from taking a brief look at how tapes work with tree addressing, we haven't discussed why these differ or how text works more broadly.

For one thing, there are four basic ways to represent text in Urbit:

@t, acord, which is an atom (single value)@ta, aknotor ASCII text, which is an atom (single value)@tas, atermor ASCII text symboltape, which is a(list @t)

This is more ways than many languages support: most languages simply store text directly as a character array, or list of characters in memory. This most closely approximates a tape.

@t cordWhat is a written character? Essentially it is a representation of human semantic content (not sound strictly). (Note that I do not refer to alphabets, which prescribe a particular relationship of sound to symbol: there are ideographic and logographic scripts, syllabaries, and other representations. Thus, characters not letters.) Characters can be composed—particularly in ideographic languages like Chinese.

One way to handle text is to assign a code value to each letter, then represent these as subsequent values in memory:

65 83 67 73 73

A S C I IThe numeric values used for each letter are the ASCII standard, which defines 128 unique characters (2⁷ = 128).

ASCII

The American Standard Code for Information Interchange was developed to allow digital devices to communicate over telecomms interfaces in the 1960s. It has since become the de facto standard for representing the basic Latin alphabet.

Unfortunately, ASCII doesn't support enough characters in 2⁷ slots to represent many diacritics and special characters, standard in many languages. This led to a longstanding but unsatisfactory system of code pages and ultimately to Unicode.

Code page 437, for instance, is frequently known as "extended ASCII" and will look familiar to anyone who has worked with DOS, OS/2, or other pre-Windows IBM-compatible systems. (I practically had this memorized back when I started programming.)

It's very helpful to use the @ux aura if you are trying to see the internal structure of a cord. Since the ASCII values align at the 8-bit wide characters, you can see each character delineated by a hexadecimal pair.

> `@ux`'HELLO'

0x4f.4c4c.4548

> `@ub`'HELLO'

0b100.1111.0100.1100.0100.1100.0100.0101.0100.1000You can think of this a couple of different ways. One way is to simple think of them as chained together, with the first letter in the rightmost position. Another is to think of them as values multipled by a “place value”:

| Letter | ASCII | Place | “Place Value” |

|---|---|---|---|

H |

0x48 | 0 | 2⁰ = 1 → 0x48 |

E |

0x45 | 1 | 2⁸ = 256 = 0x100 → 0x4500 |

L |

0x4c | 2 | 2¹⁶ = 65.536 = 0x1.0000 → 0x4c.0000 |

L |

0x4c | 3 | 2²⁴ = 16.777.216 = 0x100.0000 → 0x4c00.0000 |

O |

0x4f | 4 | 2³² = 4.294.967.296 = 0x1.0000.0000 → 0x4f.0000.0000 |

This way, each value slots in after the preceding value.

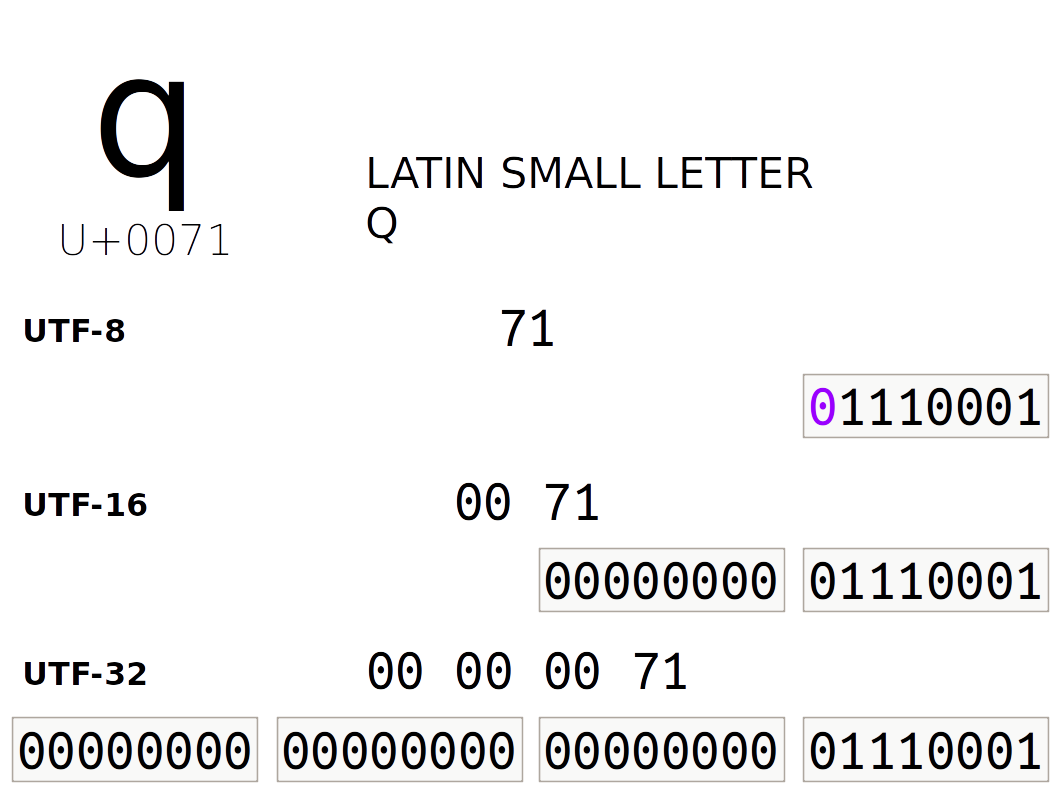

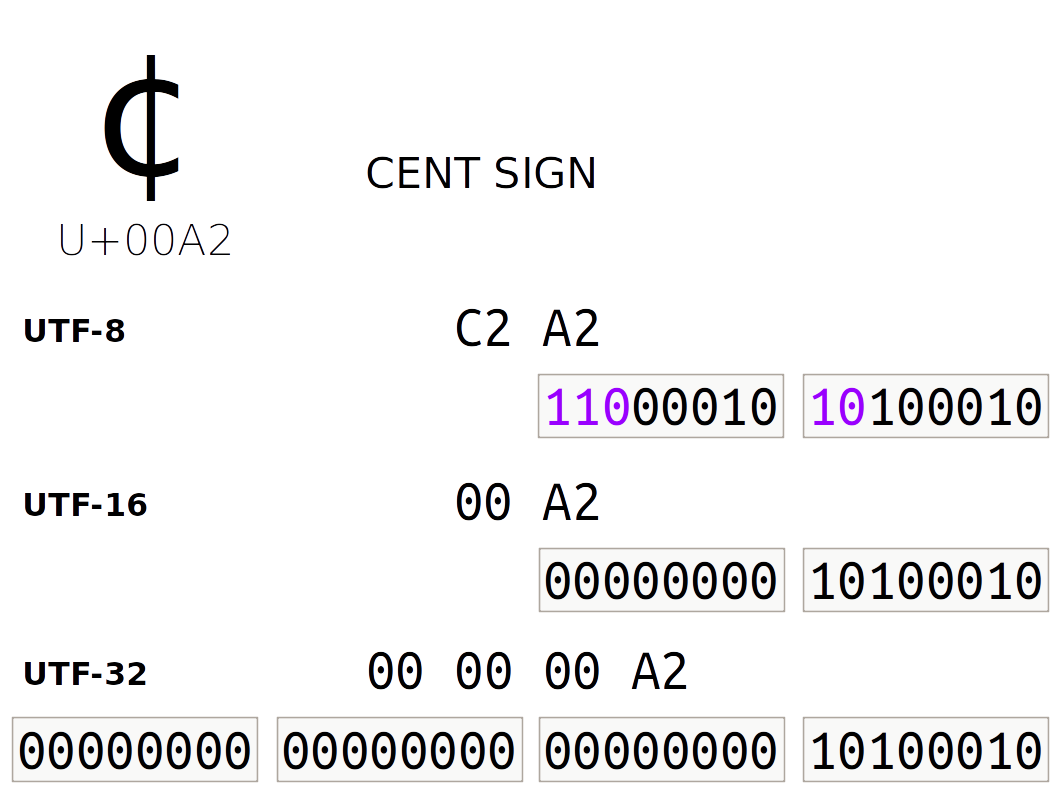

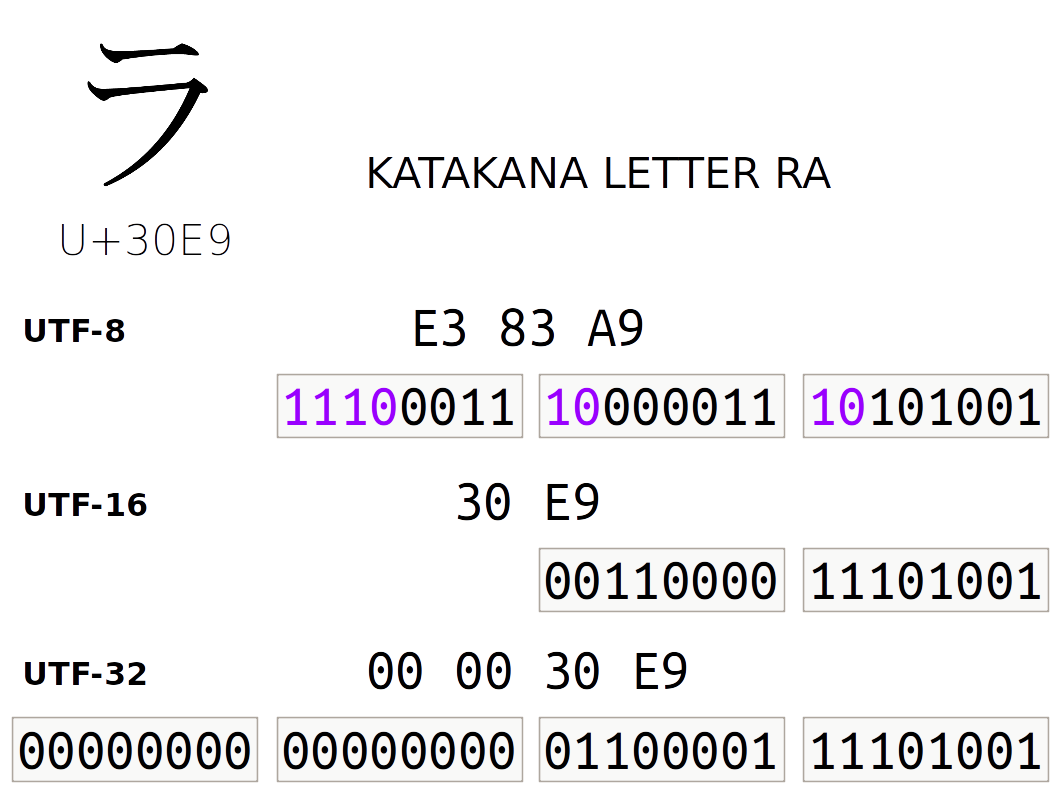

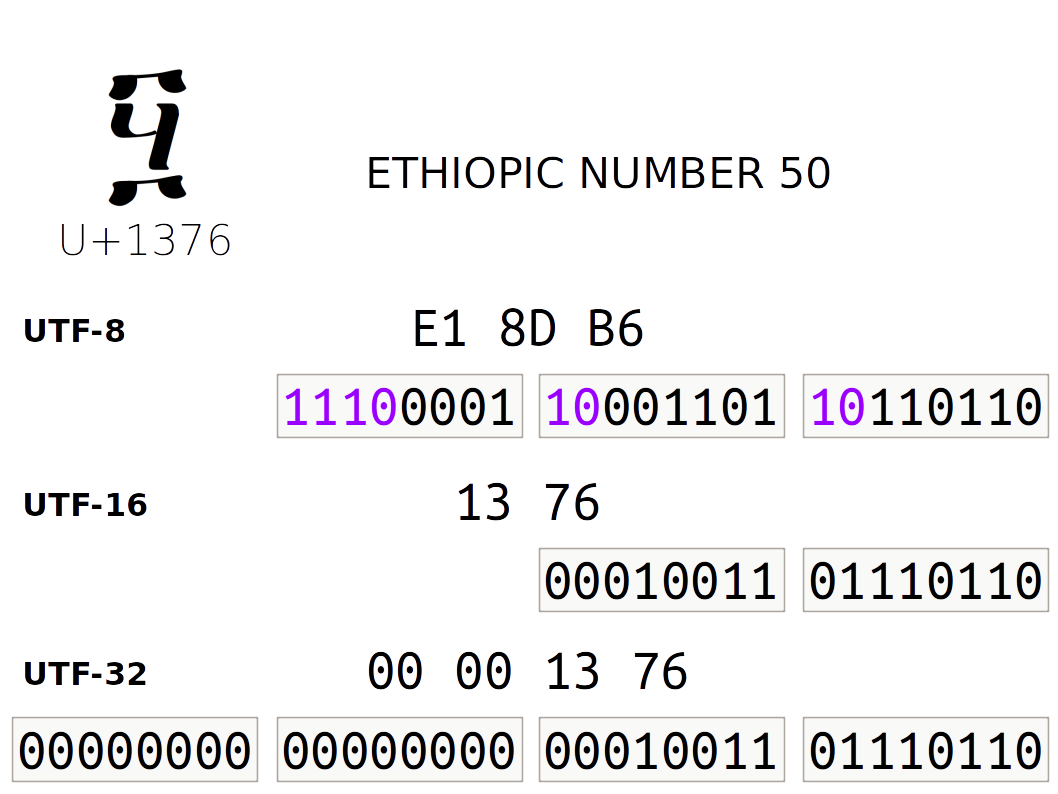

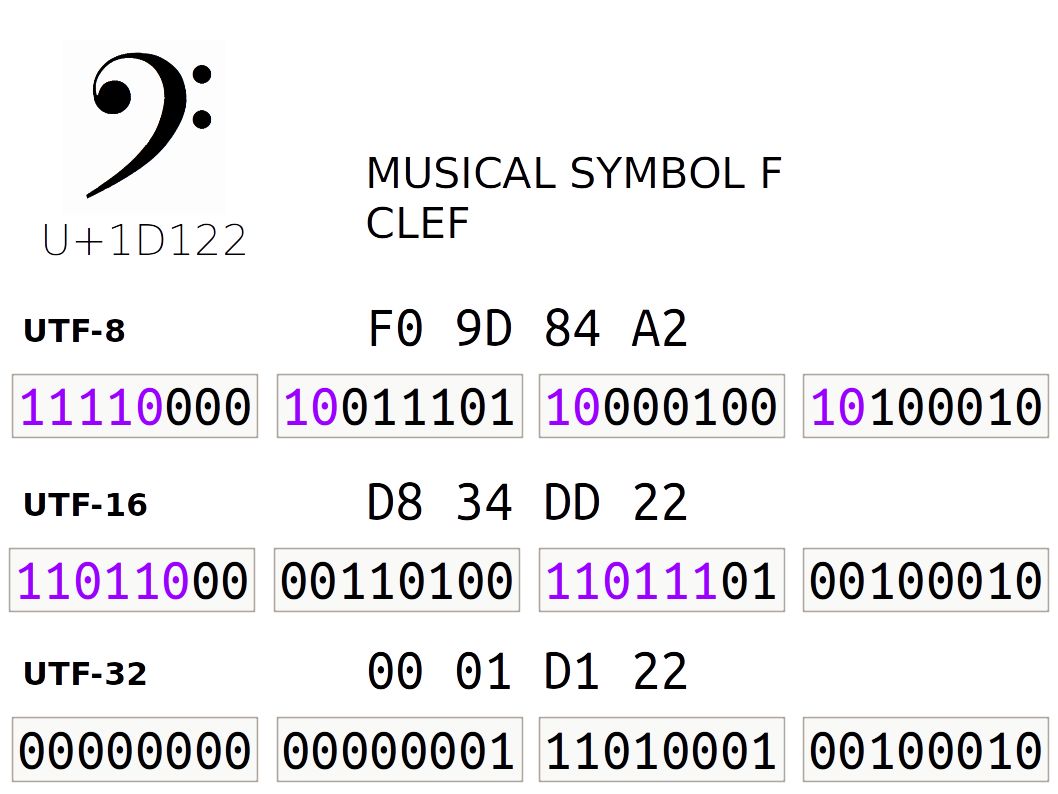

Special characters (non-ASCII, beyond the standard keyboard, basically) are represented using a more complex numbering convention. Unicode defines a standard specification for code points or numbers assigned to characters, and a few specific bitwise encodings (such as the ubiquitous UTF-8).

Urbit uses UTF-8 for @t values (thus both cord and tape).

Unicode (A Brief Aside)

Unicode separates code points from encoding. Unicode only

specifies the former.

U+010F ď LATIN SMALL LETTER D WITH CARONUnicode defines a codespace of 1,114,112 code points in the

range 0x0 to 0x10.ffff. There are about 170,000 characters

specified currently.

UTF-8 is a variable- byte encoding, using one to four bytes to represent any

possible Unicode address. The first part of UTF-8 matches

ASCII so they are intercompatible with each other.

Mojibake, the result of interpreting text with the wrong encoding (pronounce it mo-ji-ba-ke)

Big list of naughty strings, strings that tend to cause encoding and parsing problems with many software packages and libraries.

{: .callout}

(list @t) tapeThere are some tools to work with atom cords of text, but most of the time it is more convenient to unpack the atom into a tape. A tape splits out the individual characters from a cord into a list of @t values.

We've hinted a bit at the structure of lists before; for now the main thing you need to know is that they are cells which end in a ~ sig. So rather than have all of the text values stored sequentially in a single atom, they are stored sequentially in a rightwards-branching binary tree of cells.

Lists

There are many tools for manipulating text using standard

string tools. We'll take a look at those in the next major

section after “Text”.

Later on, we'll look at how to convert between the forms of text and the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Can You Trick Hoon?

If a ~ marks the end of a tape, can it occur earlier in the tape? (Make sure to distinguish the character ~ from the value ~.)

Solution

> `(list @t)`['a' 'b' ~ ~]

mint-nice

-need.?(%~ [i=@t t=*''])

-have.[@t @t %~ %~]

nest-fail

dojo: hoon expression failed@ta knot

If we restrict the character set to certain ASCII characters instead of UTF-8, we can use this restricted representation for system labels as well (such as URLs, file system paths, permissions). @ta knots and @tas terms both fill this role for Hoon.

> `@ta`'hello'

~.helloEvery valid @ta is a valid @t, but @ta does not permit spaces or a number of other characters. (See ++sane, discussed below.)

@tas term

A further tweak of the ASCII-only concept, the @tas term permits only “text constants”, values that a restricted text atom for Hoon constants. The only characters permitted are lowercase ASCII letters, -, and 0-9, the latter two of which cannot be the first character. The syntax for @tas is the text itself, always preceded by %. The empty @tas has a special syntax, $.

terms are rarely used for message-like text, but they are used all the time for internal labels in code. They differ from regular text in a couple of key ways that can confuse you until you're used to them.

For instance, a @tas value is also a mold, and the value will only match its own mold, so they are commonly used with type unions to filter for acceptable values.

> ^- @tas %5

mint-nice

-need.@tas

-have.%5

nest-fail

dojo: hoon expression failed

> ^- ?(%5) %5

%5For instance, imagine creating a function to ensure that only a certain classical element can pass through a gate:

|= input=@t

=<

(validate-element input)

|%

+$ element ?(%earth %air %fire %water)

++ validate-element

|= incoming=@t

%- element incoming

--Text Operations

The most common needs for text-based data in programming are to produce text, manipulate text, or analyze text.

Producing Text

String interpolation puts the result of an expression into a tape:

> "{<(add 5 6)>} is the answer."

"11 is the answer."++weld can be used to glue two tapes together:

> (weld "Hello" "Mars!")

"HelloMars!"|= [t1=tape t2=tape]

^- tape

(weld t1 tManipulating Text

Common operations include:

++crip: converttapeto cord (tape→cord)++trip: convertcordto tape (cord→tape)++cass: convert upper-case text to lower-case (tape→tape)++cuss: convert lower-case text to upper-case (tape→tape)

Analyzing Text

You can:

Search

Tokenize

Convert into data

Search

++find[nedl=(list) hstk=(list)]locates a sublist (nedl, needle) in the list (hstk, haystack)

Count the Number of Characters in Text

There is a built-in ++lent function that counts the number of characters in a tape. Build your own tape-length character counting function without using ++lent.

You may find the ?~ wutsig rune to be helpful. It tells you whether a value is ~ or not. (How would you do this with a regular ?: wutcol?)

Tokenize/Parse

To tokenize text is to break it into pieces according to some rule. For instance, to count words one needs to break at some delimiter.

The full parser for Hoon text is very sophisticated. There are a lot of rules to deciding what is and isn't a rune, and how the various parts of an expression relate to each other. (Remember !, zapcom?) We don't need that level of power to work with basic text operations, so we'll instead use basic list tools whenever we need to extract or break text apart.

Parsing Text

Hoon has a very powerful text parsing engine, built to compile Hoon itself. However, it tends to be quite obscure to new learners. We can build a simple one using list tools, as you'll see in the next section.

Convert

If you have a Hoon value and you want to convert it into text as such, use ++scot and ++scow. These call for a value of type $dime, which means the @tas equivalent of a regular aura. These are labeled as returning cords (@ts) but in practice seem to return knots (@tas).

++scot: renderdimeascord(dime→cord); include any necessary aura transformation.

> `@t`(scot %ud 54.321)

'54.321'

> `@t`(scot %ux 54.000)

'0xd2f0'

> (scot %p

~sampel-palnet

)

~.~sampel-palnet

> `@t`(scot %p

~sampel-palnet

)

'~sampel-palnet'++scow: renderdimeastape(dime→tape); otherwise identical to++scot.

++sane is used to check the validity of a possible text string as a knot or term. The usage of ++sane will feel a bit strange to you: it doesn't apply directly to the text you want to check, but it produces a gate that checks for the aura (as %ta or %tas). (The gate-builder is a fairly common pattern in Hoon.) ++sane is also not infallible yet.

> ((sane %ta) 'ångstrom')

%.n

> ((sane %ta) 'angstrom')

%.y

> ((sane %tas) 'ångstrom')

%.n

> ((sane %tas) 'angstrom')

%.yWhy is this sort of check necessary? Two reasons:

@taknots and@tasterms have strict rules, such as being ASCII-only.Not every sequence of bits has a conversion to a text representation. That is, ASCII and Unicode have structural rules that limit the possible conversions which can be made. If things don't work, you'll get a %bad-text response.

> 0x1234.5678.90ab.cdef

0x1234.5678.90ab.cdef

[%bad-text "[39 239 205 171 144 120 86 52 92 49 50 39 0]"]There's a minor bug in Dojo that will let you produce an erroneous term (@tas):

> `@tas`'hello mars'

%hello marsSince a @tas cannot include a space, this is formally incorrect, as ++sane reveals:

> ((sane %tas) 'hello')

%.y

> ((sane %tas) 'hello mars')

%.nList Operations

The tape is a special kind of list, actually a (list @t). Other lists can contain other atom types, generic atoms, other lists (lists of lists), or even generic nouns.

A list is an ordered arrangement of elements ending in a ~ (null). Most lists have the same kind of content in every element (for instance, a (list @rs), a list of numbers with a fractional part), but some lists have many kinds of things within them. Some lists are even empty.

> `(list @)`['a' %b 100 ~]

~[97 98 100](Notice that all values are converted to the specified aura, in this case the empty aura.)

A list is built with the list mold. (Remember that a mold is a type and can be used as an enforcer: it attempts to convert any data it receives into the given structure, and crashes if it fails to do so.)

Lists are commonly written with a shorthand ~[]:

> `(list)`~['a' %b 100]

~[97 98 100]> `(list (list @ud))`~[~[1 2 3] ~[4 5 6]]

~[~[1 2 3] ~[4 5 6]If something has the same structure as a list but hasn't been explicitly labeled as such, then Hoon won't always recognize it as a list. In such cases, you'll need to explicitly mark it as such:

> [3 4 5 ~]

[3 4 5 ~]

> `(list @ud)`[3 4 5 ~]

~[3 4 5]

> -:!>([3 4 5 ~])

#t/[@ud @ud @ud %~]

> -:!>(`(list @ud)`[3 4 5 ~])

#t/it(@ud)](See also ++limo which marks a null-terminated tuple as a list.)

Using ~[] still doesn't mark it as a list, unfortunately, which can lead to some confusion:

> -:!>(~['a' %b 100])

#t/[@t %b @ud %~]

> -:!>(`(list)`~['a' %b 100])

#t/it(*)Notice that the type from the type spear -:!> shows up as it(), short for an “iterator”, or type that can potentially continue as long as the pattern matches.

What is the Structure of a list of lists?

Draw a binary tree representing the actual tree location of

values in this data structure:

`(list (list @ud))`~[~[1 2 3] ~[4 5 6] ~[7 8 9]]Once you have your data in the form of a list, there are a lot of tools to manipulate and analyze them:

++flopreverses the order of the elements (exclusive of the~):

> (flop ~[1 2 3 4 5])

~[5 4 3 2 1]++sortuses alistand a comparison function (like++lth) to order things:

> (sort ~[1 3 5 2 4] lth)

~[1 2 3 4 5]++snagtakes a index and a list to grab out a particular element (note that it starts counting at zero):

> (snag 0 `(list @)`~[11 22 33 44])

11

> (snag 1 `(list @)`~[11 22 33 44])

22

> (snag 3 `(list @)`~[11 22 33 44])

44

> (snag 3 "Hello!")

'l'

> (snag 1 "Hello!")

'e'

> (snag 5 "Hello!")

'!'There are a couple of sometimes-useful list builders:

++gulfspans between two numeric values (inclusive of both):

> (gulf 5 10)

~[5 6 7 8 9 10]++reaprepeats a value many times in alist:

> (reap 5 0x0)

~[0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0]

> (reap 8 'a')

<|a a a a a a a a|>

> `tape`(reap 8 'a')

"aaaaaaaa"

> (reap 5 (gulf 5 10))

~[~[5 6 7 8 9 10] ~[5 6 7 8 9 10] ~[5 6 7 8 9 10] ~[5 6 7 8 9 10] ~[5 6 7 8 9 10]] Once you have a list (including a tape), there are a lot of manipulation tools you can use to extract data from it or modify it:

++find[nedl=(list) hstk=(list)]locates a sublist (nedl, needle) in the list (hstk, haystack)++snag[a=@ b=(list)]produces the element at an index in the list (zero-indexed)++snap[a=(list) b=@ c=*]replaces the element at an index in the list (zero-indexed) with something else++scag[a=@ b=(list)]produces the first a elements from the front of the list++slag[a=@ b=(list)]produces the last a elements from the end of the list++weld[a=(list) b=(list)]glues twolists together (not a single item to the end)

There are a few more that you should pick up eventually, but these are enough to get you started.

Using what we know to date, most operations that we would do on a collection of data require a trap. However, there are some cool aggregators and applicators:

++roll[a=(list) b=gate]slams a two-argument gate from left to right across a list.For instance, to obtain the sum of a list of numbers, use it with

++add:(roll (gulf 1 5) add)You could even build a factorial this way:

|= n=@ud (roll (gulf 1 n) mul)(Due to internal optimizations, this is actually much faster than the ones we have written to date!)

++turn[a=(list) b=gate]produces a new list with the gate applied to each element of the original.(turn (gulf 65 90) @t)Include the factorial function from a moment ago:

(turn (gulf 1 20) factorial)

A few operations in Hoon actually require a lest, a list guaranteed to be non-null (that is, ^- (list) ~ is excluded).

> =/ list=(list @) ~[1 2 3]

i.list

-find.i.list

find-fork

dojo: hoon expression failedThis can be done by testing whether the value is null, either directly with ?: wutcol or using the specialized ?~ wutsig rune.

> =/ list=(list @) ~[1 2 3]

?~ list !!

i.list

1Break Text at a Space

Let's build a parser to split a long tape into smaller tapes at single spaces. That is, given a tape

"the sky above the port was the color of television tuned to a dead channel"

the gate should yield

~["the" "sky" "above" "the" ...]

To complete this, you'll need ++scag and ++slag (who sound like villainous henchmen from a children's cartoon.

Solution

=/ ex "the sky above the port was the color of television tuned to a dead channel"

=/ index 0

=/ result *(list tape)

|- ^- (list tape)

?: =(index (lent ex))

result

?: =((snag index ex) ' ')

$(index 0, ex `tape`(slag +(index) ex), result (weld result ~[`tape`(scag index ex)]))

$(index +(index))=/ ex "the sky above the port was the color of television tuned to a dead channel"

=/ index 0

=/ result *(list tape)

|-

?: =(index (lent ex)) result

:: one case is this is a regular character

:: one case is this is a space

?: =(' ' (snag index ex))

%= $

index +(index)

result (weld result (scag index ex))

==

$(index +(index))Building Your Own Library

As an addendum to our discussion about cores last week, let's take some of the code we've built above for processing text and turn them into a library we can use in another generator.

Build a Library

Take the space-breaking code and the element-counting code gates from above and include them in a |% barcen core. Save this file as lib/text.hoon in the %base desk and commit.

Produce a generator gen/text-user.hoon which accepts a tape and returns the number of words in the text (separated by spaces). (How would you obtain this from those two operations?)

Logging

The most time-honored method of debugging is to simply output relevant values at key points throughout a program in order to make sure they are doing what you think they are doing. For this, we introduced ~& sigpam recently.

The ~& sigpam rune offers some finer-grained output options than just printing a simple value to the screen. For instance, you can use it with string interpolation to produce detailed error messages.

There are also > modifiers which can be included to mark “debugging levels”, really just color-coding the output:

1. No >: regular

2. >: information

3. >>: warning

4. >>>: error(Since all ~& sigpam output is a side effect of the compiler, it doesn't map to the Unix stdout/stderr streams separately; it's all stdout.)

You can use these to differentiate messages when debugging or otherwise auditing the behavior of a generator or library. Try these in your own Dojo:

> ~& 'Hello Mars!' ~

~

> 'Hello Mars!'

> ~& > 'Hello Mars!' ~

~

>> 'Hello Mars!'

> ~& >> 'Hello Mars!' ~

~

>>> 'Hello Mars!'

> ~& >>> 'Hello Mars!' ~

~